-

-

- 2018-2019 Preseason:

Fan Bereavement Over A NFL Crowning Achievement?

-

-

-

-

This edition of "The Tortured

Cowboys Fan" has also been published by the fine folks at

Sports TalkLine.

-

-

-

-

-

September 2, 2018 At 4:00 AM CST

By Eric M. Scharf-

- Roquan Smith finally ended his 29-day holdout when he signed a

4-year, $18.4M contract with the Chicago Bears on Monday, August

13th, 2018. It was a momentous occasion for regional

prognosticators, perpetually hopeful Bears fans in search of their

next great linebacker, and fantasy footballers eager for something

new to discuss.

This story – at first glance – was a quick read. The Bears drafted a

first-round talent whom they see as a key piece to the puzzle that

inches them significantly closer to their old reputation as the

“Monsters of the Midway.” The rookie’s handlers felt equally

determined that Smith’s $11.5M signing bonus needed to be

significantly closer to setting a hands-off precedent in the face of

the NFL’s new-for-2018 targeting rule. The Bears – to a good degree

– acquiesced, and Roquan’s path to payment may prove a useful

contract negotiation tool.

The new rule – approved in March of this year – is designed to

fortify other existing player-safety measures, and it mimics a

similar game day rule established by the NCAA. When ANY offensive or

defensive player lowers his head to initiate contact with an

opposing player, there will be an automatic 15-yard penalty. While

it seems wise of the league to have avoided specifying “crown of the

helmet” – even though such penalties in preseason have thus-far been

levied at light speed – a replay delay of epic proportions may still

be in the regular season offing.

-

- Nonetheless, the salary cap era – along with first-ever,

contract-acknowledged signing bonuses – was introduced to the NFL in

1994. After surviving the San Francisco 49ers’ brutal exploitation

of early signing bonus loopholes, the concept of partial,

conditional guarantees of signing bonuses would slowly develop over

the last 24 years. This would lead to modern day negotiating

conditions in which representatives of first round draft picks now

feel (even more) compelled to play chicken with what they hope is an

organization more in-need than the players they represent.

“What is so incredibly different about this? Players hold out all

the time – in the NFL and other professional team sports – demanding

more money, more reasonably-achievable incentives, greater

front-loaded contract guarantees over fewer years. Why should anyone

care?” you ask.

This story – for discerning football fans – is anything but brief.

Roquan Smith is merely the newest bit player in the latest act of an

NFL screenplay that has been unfolding since August 20th, 1920. The

challenge goes much deeper than any demands for protection over a

given player’s signing bonus from that player’s temporary or

permanent inability to perform his job . . . without (increasingly)

going awry of the NFL’s player-safety rules like a practice squad

slob.

Examples So Ample

The NFL had long-celebrated incredible kill shots – applied both

offensively and defensively – to devastating, even career-ending

effect. “NFL Films” – among its decades of rich content – has more

than a few player-punishing presentations. Fans (most but not all)

love to see cross-eyed collisions – especially following turnovers –

between aware and seemingly oblivious players (who are repeatedly

coached to “beware the drivel and keep your head on a swivel”).

Kill shots are not just aimed at the quarterback’s blindside, the

diminutive slot receiver crossing over the middle, or the kick

returner (who can no longer hide behind a violent special teams

wedge). Players get their bells rung by opponents of all shapes,

sizes, and roles . . . from intentional to accidental, with almost

every result being painfully influential.

-

- Dick "The Maestro of Mayhem” Butkus, “Mean” Joe Greene, Dick “Night

Train” Lane, Jack “Dracula In Cleats” Lambert, Chuck "Concrete

Charlie" Bednarik, Jack "The Assassin" Tatum, Ray Lewis, and Deacon

"Head Slap" Jones were all consistently among the NFL’s meanest . .

. and provocative defenders with whom only the brave or ignorant

ever messed. And Bednarik was – perhaps – the last of the

(trouncing) two-way titans . . . and – no matter from which side of

the ball he launched – he was none too invitin’.

These players were often so fearless they might have been willing to

pursue their vicious vectors with no more than a leather cap . . .

though Randy “The Manster” White had no compunction about

obliterating an opponent – like the Bears’ Mark Bortz – with his own

teammate’s helmet when given any crap. Though it was a curious head

smasher, err, head scratcher for White, as he had years of deadly

Wing Chun, Jeet Kune Do, and the Filipino martial arts training on

tap.

Running backs may always receive just a bit more crushing credit

than their defensive counterparts for having to tote the rock while

delivering such violent smacks. If you cannot fend off defensive

harm with one good arm, you may end up buying the farm.

-

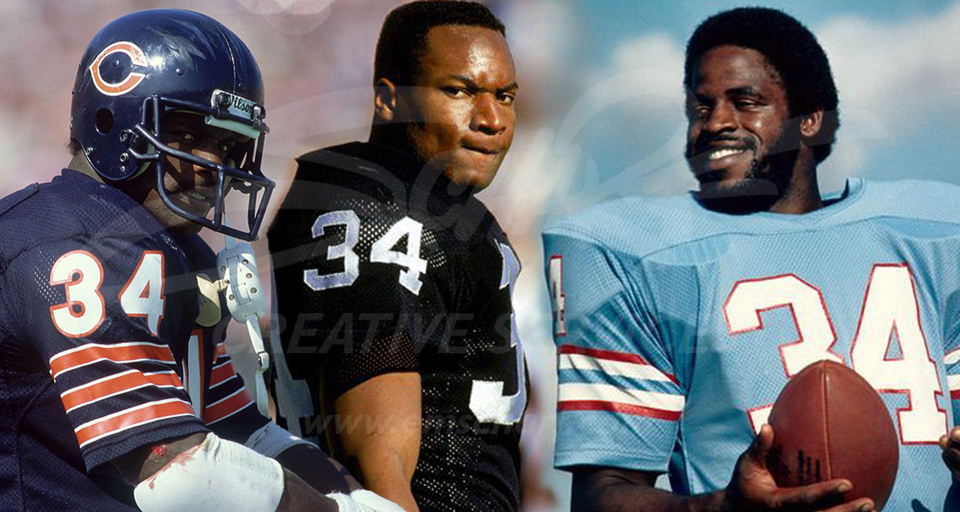

- The Houston Oilers’ Earl “The Tyler Rose” Campbell starred as

“The Human Wrecking Ball” in 1978 as he single-handedly demolished

the Los Angeles Rams’ defensive front . . . and nearly shattered the

sternum of linebacker Isiah “(Not So) Butch” Robertson with a

headbutt heard round-the-world. While Campbell was comparatively

short, he spent most of his career battering defenders into

tenderized runts.

When the Bears’ Walter "Sweetness" Payton was not busy deftly

outmaneuvering and anvil-smashing, err, sidearm-shivering opponents

at Soldier Field . . . he was firing his head and shoulders into

defenders like a trophy hunter pursuing an endangered species with a

successful yield.

Cleveland’s Jim Brown spent most of his amazing career simply mowing

down defenders with a body carved from granite. He almost never had

to “tip his (hardened) cap,” with so many opponents screaming

“Enough! We’ve had it!”

The San Francisco 49ers’ Roger Craig would high-step between the

tackles at Candlestick Park like a bighorn sheep on Broadway . . .

with his knees up, head down, and ready to pound out a rhythm on

every play.

The New York Giants’ Otis Anderson may have been a slow, plodding

ball-carrier, but he led with an uppercut, err, wide-swinging

forearm that successfully cleared almost any defensive crowd . . .

surely making even heavyweight boxer George Foreman proud.

Bruising ball-carriers Bo Jackson, Adrian Peterson, John Riggins,

Herschel Walker, Marshawn Lynch, Frank Gore, Brandon Jacobs, Eddie

George, Mike Alstott, and Steven Jackson would regularly (and often

successfully) attempt to truck opponents into submission – using a

combination of helmets, shoulder pads, forearms, stiff arms, and

knees – with only Marshawn Lynch still in a starting position to

deliver such a destructive thrill.

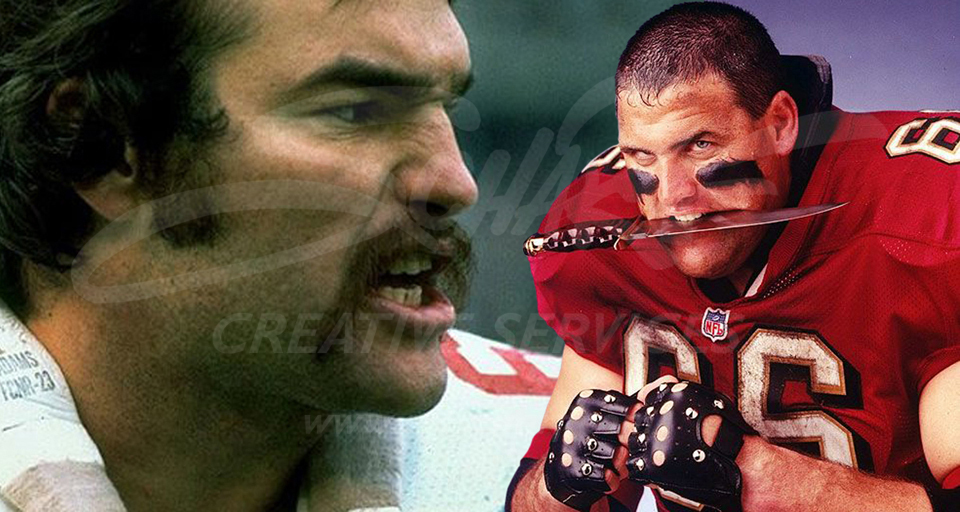

Conrad "Dominican Dracula" Dobler and Kevin "Big Nasty" Gogan and

their common "anything goes (on the offensive line)" style of play .

. . included plenty of biting, leg whips, and trips regardless of

whether officials were looking the other way.

-

- Browns strong safety Felix Wright – during a 1990 playoff game in

Cleveland – upended Bills receiver Don Beebe who landed quite

uncomfortably on his head. He - to this day – is thankful not to be

dead.

During Super Bowl XXXII in 1998, the Broncos' Steve Atwater and

Randy Hilliard crashed crowns . . . with their mutual target -

Packers receiver Robert Brooks - barely ducking down.

Tampa Bay defensive tackle Warren Sapp blew up Green Bay offensive

tackle Chad Clifton in 2002, and it took that pummeled Packer over

six grueling months to prove he was not through.

Cowboys Roy "Strong Safety" Williams applied a horse collar in 2004 . . . gifting Eagles receive Terrell Owens some

unintended broken leg gore.

Cardinals receiver Anquan Boldin was helmet-hammered by Jets safety

Eric Smith in 2008. While Smith was deservedly seeing stars for the

days that would follow, Boldin came away with a sinus fracture that

– for anything more than protein shakes – made it hard to chew and

swallow.

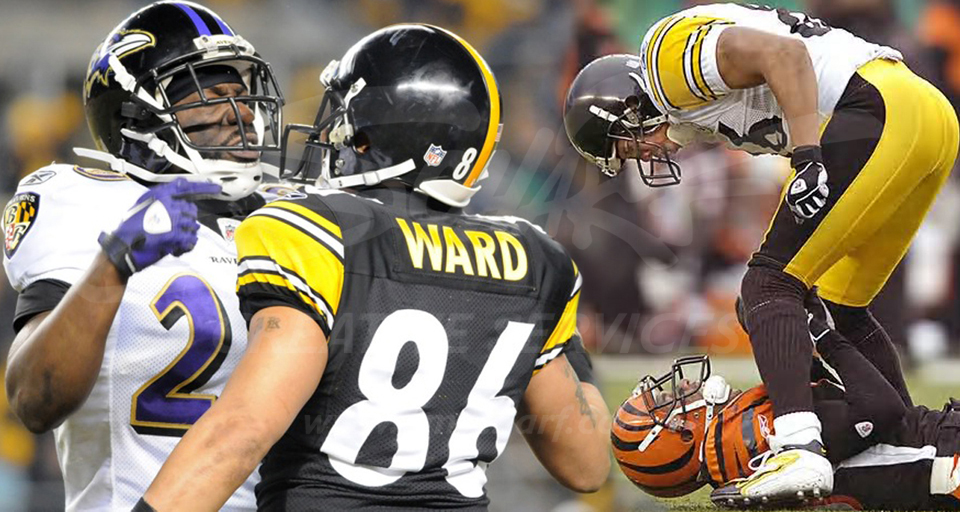

Steelers receiver Hines Ward mercilessly mangled Bengals' linebacker

Keith Rivers in 2008 . . . and he did it again to Ravens' preeminent

ball hawk Ed Reed in 2010, shamelessly encouraging more rivalry

hate.

-

- Albert "Gurode Goring" Haynesworth (in 2006 against Dallas) took a

step in the wrong direction . . . while Ndomakong "Damaging

Dietrich-Smith" Suh (in 2011 against Green Bay) appeared to suffer

from the same brain infection.

Seahawks receiver Golden Tate – during a 2012 Seattle home game –

sideswiped Cowboys linebacker Sean Lee before he could zero in on

Russell Wilson. It was an understatement to say Lee pulled up lame.

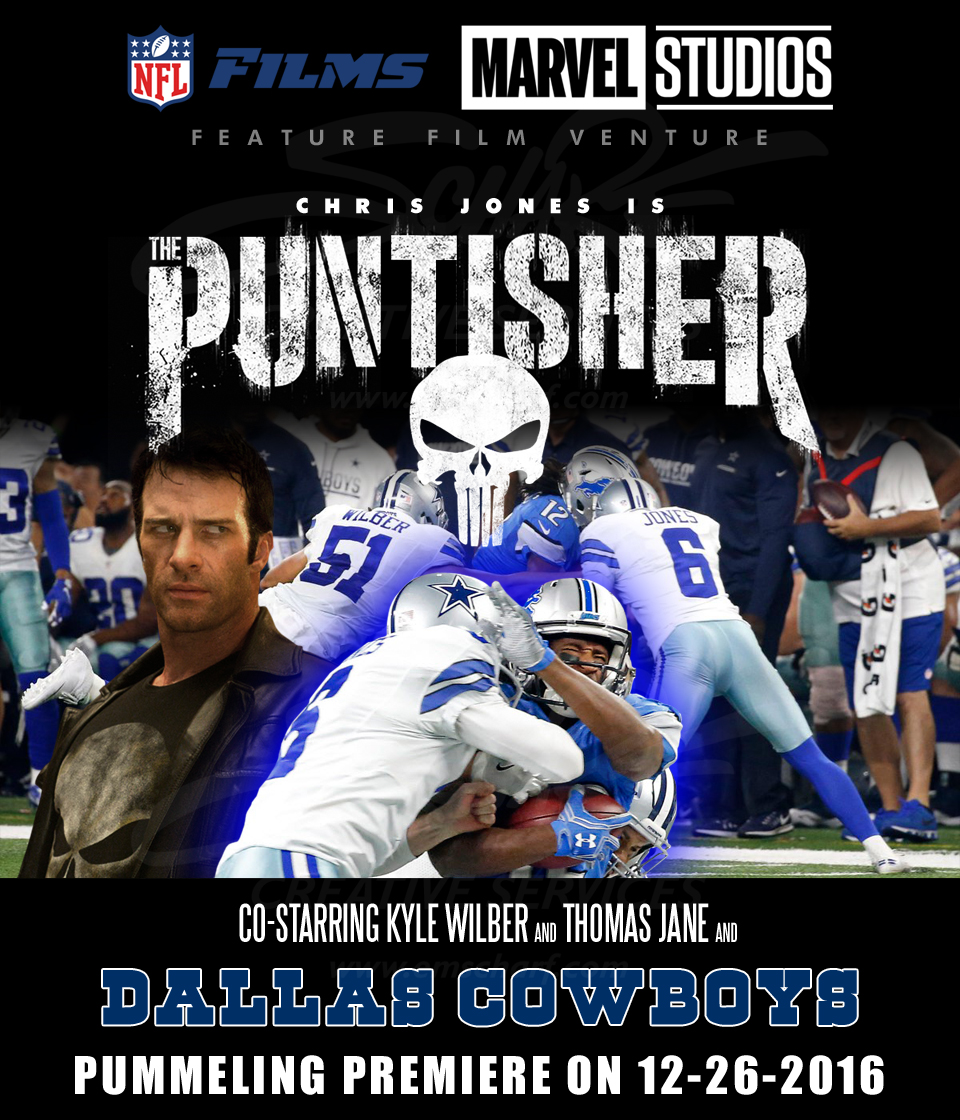

Cowboys punter Chris "The Puntisher" Jones (with a mild assist from

linebacker Kyle Wilber) performed a sideline slam of Lions return

man Andre Roberts in 2016.

-

- And for every frustration-forced, purposeful plunge in 2017 by a

Danny Trevathan or a Vontaze Burfict . . . there is a Ryan Shazier

accident-turned-tragedy that draws even more scrutiny over the NFL’s

heads-down defect.

The number of ways in which NFL players choose to bring the pain to

each other – by relying so much on raw physique that it smothers

quality technique (or repeatedly going in a lowdown direction to

risk team-choking ejection) – are practically unending . . . and if

the NFL and NFLPA are not careful, the (increasing) fallout could be

mind-bending.

Choice

The helmet is clearly one of many tools regularly used to be

physically cruel, but the choice to increasingly use a helmet –

above all other methods – is what has (in part) triggered the

seemingly knee-jerk implementation of the NFL’s targeting rule.

The NFL Competition Committee previously introduced a defenseless

player rule. The targeting rule simply reinforces and adds a layer

to what was established for a defenseless player.

Such cataclysmic events will never entirely fade into the past,

though some would argue the majority of them must eventually

disappear for the NFL to enjoy significant growth and truly last.

The best of intentions – albeit driven by massive legal fears – have

resulted in a couple take-your-medicine rules . . . designed to

discourage any further death-defying fools.

The NFL had little choice when facing the toxic combination of (1)

players who (still) fancy themselves “Concussion Knievel’s,” (2)

exposure of the NFL’s long-pursued efforts to suppress any

connection between repeated blunt force trauma and the development

of CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy) in any football player’s

brain . . . and (3) the unsettling conditions of the “settled”

concussion lawsuit brought by former NFL players that has added to

the league’s (current) publicity stain.

Nonetheless and following Roquan Smith’s fresh-if-indirect addition

to the NFL’s tackling tale, there very well could be a

quickly-growing number of players – whether through their own

understanding or at the urging of their agents – who would rather

insist their bonuses be shielded from their own technical laziness .

. . than make a conscious, coachable effort to rise above this

helmet craziness.

Some NFLPA members will acknowledge that – even in such a violent

sport – the choice still overrides the technique learned under years

of tutelage . . . and other union brothers will insist their

“successful methods” are being hindered by what amounts to player

safety garbage.

Quality wrap-up tackling – for years now – has been on the verge of

going the way of the dodo bird or the NBA’s intermediate jump shot

and “free throw” . . . which are blindfolded breezes for old school,

technique-heavy players but “challenging” for many of the modern

day, physically superior, and mentally or playbook slow.

Defensive players will also (somewhat privately) concede that no

longer leading with their helmets also exposes them as either

workout warriors and tackling frauds (like Vernon Gholston) or real

students of the game, true technical gods. Defenders who are not the

most coachable or possess that 3M (Minimum Magic Mix) of football

skills every NFL team seeks . . . are left to hitting opponents as

hard as possible in a cover-up effort that inevitably wreaks.

-

- For every clobbering cornerback, there was a supremely fast Deion

Sanders and a unbearably slow Everson Walls . . . both of whom

almost always managed to get to the offensively-diagramed spot

before receivers even finished digesting the play calls. They could

have been physically belligerent but – more often than not – they

chose to be more intelligent.

For every destroying defensive lineman, there was a Ed “Too Tall”

Jones . . . big and unfairly tall with a heavyweight boxer’s wing

span, who could bat down passes or reach the quarterback without

(purposely) leaving his feet (to decapitate or torpedo), and leaving

his often equally-talented teammates to pick over the bones. He

could have been physically belligerent but – more often than not –

he chose to be more intelligent.

-

- For every leveling linebacker, there is a Luke Kuechly or a Sean Lee

. . . who triangulate so fast and furiously towards their targets

that opponents know it is pointless to flee. They could be

physically belligerent but – more often than not – they choose to be

more intelligent.

Offensive players – as with the current leanings of the NFL rulebook

– have a comparatively easy transformation . . . having to rely on

no more than sturdy shoulders and a solid stiff-arm to avoid

a possible suspension.

For every raucous running back, there was a Thurman Thomas, Marshall

Faulk, Tony Dorsett, Eric Dickerson, LaDainian Tomlinson, Barry

Sanders, and Emmitt Smith . . . where some cosmic combination of

body balance, vast vision, serious speed, sensational shiftiness,

and a sixth sense were far from a myth. They could have been

physically belligerent but – more often than not – they chose to be

more intelligent.

Leading with the helmet may, indeed, have been ingrained for some

players through questionable training (by some but not all coaches),

and that learned approach may well be impacted by heat-of-the-moment

fate, but the trajectory of that hard hat begins with a choice. A

change in player decisions – with a renewed focus on technical

precision – will give helmets less of a negative game day voice.

The transition will be reasonable for some, challenging for most,

and temporarily resisted by others who burn their paychecks like

toast. The end result will – of course – be left to the referees,

who might prefer to keep their controversial yellow hankies pocketed

more than most.

Will They Or Won’t They?

Will the helmet heresy become as polarizing to the fans as players

taking a knee during the singing of the national anthem?

Will players actually succumb to some kind of warped peer pressure .

. . once their drive-killing or possession-extending penalties

become too huge to measure?

Big picture believers will not be shocked if the NFL ultimately

decides to turn the other cheek on recapturing signing bonuses from

helmet-haunted players . . . with an eye towards fulfilling some

2021 CBA prayers.

Players want to keep (as much of) their bonus money (as possible)

even in the face of a horrifying hit. The NFLPA also wants marijuana

removed from the NFL’s list of banned substances, allowing players

to therapeutically get lit. Will the union go as far as sacrificing

more of the profit pie – in the form of owner-cherished stadium

credits – in order for these two key interests to fly?

Coaches and players (most but not all) have made it clear they feel

cramped by this helmet deal, but will there be significant fan

bereavement over the NFL’s crowning achievement?

Will the NFL regular season finally arrive . . . allowing eager fans

to see which teams will thrive and which will dive?

We shall see. We always do.

|