-

-

- 2009 Film Review - Watchmen

-

-

-

- April 1,

2009

- By Eric M. Scharf

-

- "The Media Magnate" has been a comic book fan for

years, particularly of those books that successfully marry quality

visuals and robust story-telling, filled with one gut-wrenching

irony after another . . . where vulnerability and humanity are always

right on the heals of the impossible and the unimaginable.

The Media Magnate has been waiting for just as many years to see the film industry

finally develop the nerve or be convinced of the financial

incentive to begin bringing many of the grittier, more mature,

comic book-derived themes to the silver screen.

The desired transformation began the moment the

Green Goblin cut Peter Parkers forearm in Sam Raimi's Spider-Man

in 2002 showing fans everywhere that superheroes are susceptible

to (all or instances of) the dreaded human condition, sometimes

being vulnerable (to paying rent, being late for a date, or

desperately needing a haircut for that date) and for all their

incredible gadgets, impossible super powers, and escapist hideouts

can be generally affected like much of society.

Batman Begins arrived in 2005

supplanting fan favorite Michael Keaton's 1989 portrayal with a

slick, substantive Bruce Wayne . . . and a dynamic, deadly Dark

Knight. Christopher Nolan treated all but the most

emotionally-challenged to a long overdue departure (or Warner

Brothers apology for and) from Joel "Extra Cheese" Schumacher's "Batman

Forever" and "Batman & Robin." Moviegoers see Christian Bale's

interpretation (of the billionaire businessman) struggle to come to grips

with his own mortal limitations in being unable to protect those

closest to him, even with all of his inherited financial might. He

discovers his ultimate solution, however on his way down a

destructive and terminal path which allows him to combine his

formidable fighting skills and material resources while requiring

only one 'small' thing of himself: become more than human without becoming

inhuman. Can he maintain enough clarity to remember where to draw

the line between being a vigilante hero for the people and becoming

the very villain(s) he has sworn to stop? How dark will he become?

The Dark Knight, indeed.

300 bludgeoned its way into our lives in 2006, taking grit to an

entirely new level and creating a potential new wave of history

teachers, even if the history portrayed in this film was admittedly

enhanced for our pleasure. The mere existence of this film alone with all of its bare feet and bloody battles

is convincing enough that moviegoers will be none-the-poorer if

they never see another brazen blood bath of a horror film

again.

The term 'graphic novel' will never again simply be defined as a

bigger and better extension of good ol fashioned comic

books. Everything about a graphic novel from the length of story

to depth of plot to richness of

characters to quality of inking to pop of color to physical size to

price to

quality of paper (for both cover and pages) is and will continue to be different and

greater.

Other comic book-based films such as Iron Man in 2007 have taken a

milder-but-still-potent approach in adding to the film industrys 'personal growth' experience.

Not all comic

book-to-film adaptations to be clear (need to) involve urgent,

Thunderdome, survival of the fittest scenarios in order to better

bring them to life. The

more variety in film adaptations to match the variety of

their comic book source material the better.

The Media Magnate 'simply' wishes to watch

one (or more, many, MANY MORE) of these adaptations and leave the theater believing that these

stories, events, and characters are even reasonably possible, especially in the case of a investigation-minded, physically fit,

hand-to-hand combat-ready, weapons-trained human dressed as a costumed crime fighter. And who

among the millions of comic book (and billions of feature film) fans would not wish for the same

thing?

No such comic-book-adapted film, however, has yet gone for the gusto in the same way as has

been achieved by "Watchmen." There was plenty of incentive to see this

film and considering the same director who helmed 300, Zack Snyder,

was steering this ship there was additional intrigue to see if Mr.

Snyder would, again, push the dirty, grimy envelope or acquiesce to

film execs fearful of an always-possible public backlash for

(GASP!) another R-rated graphic novel adaptation.

After all, there is always

someone 'out there' who will be screaming Is it not enough that we

know good ole Dagwood likes big sandwiches? Do we really want to

know the kind of mammoth meat contained in his sandwiches, too?

Why, yes, WE DO.

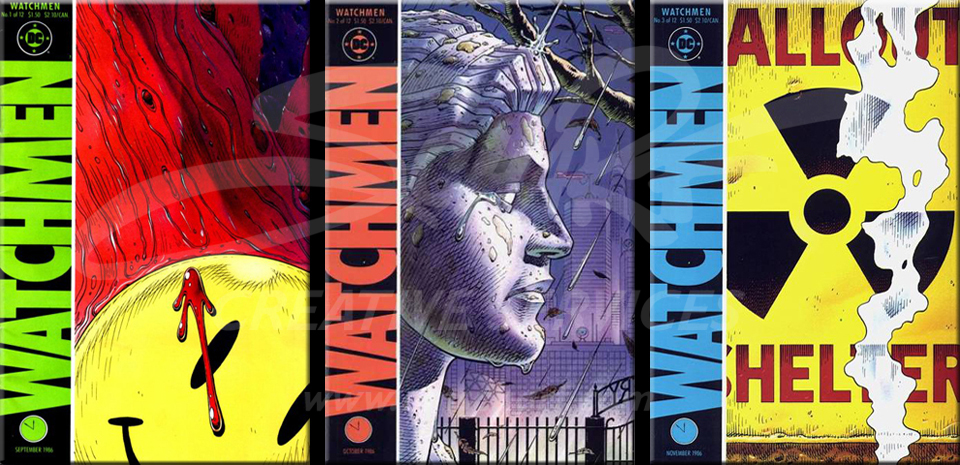

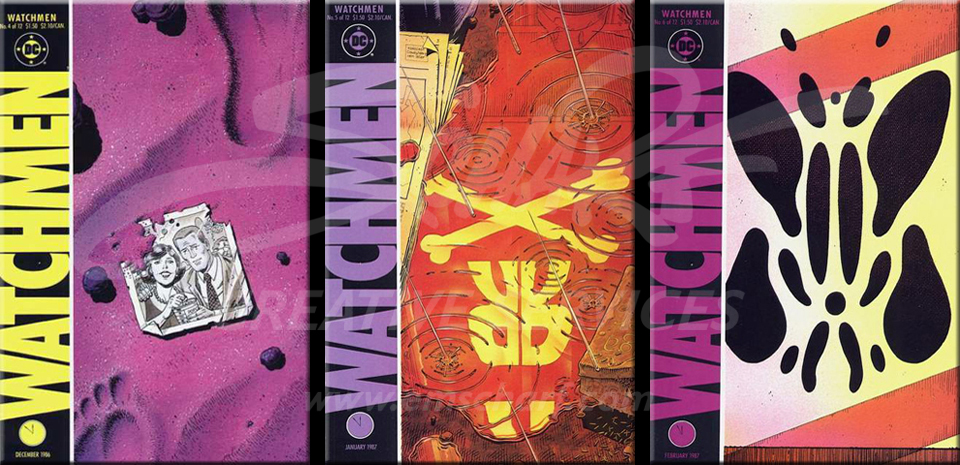

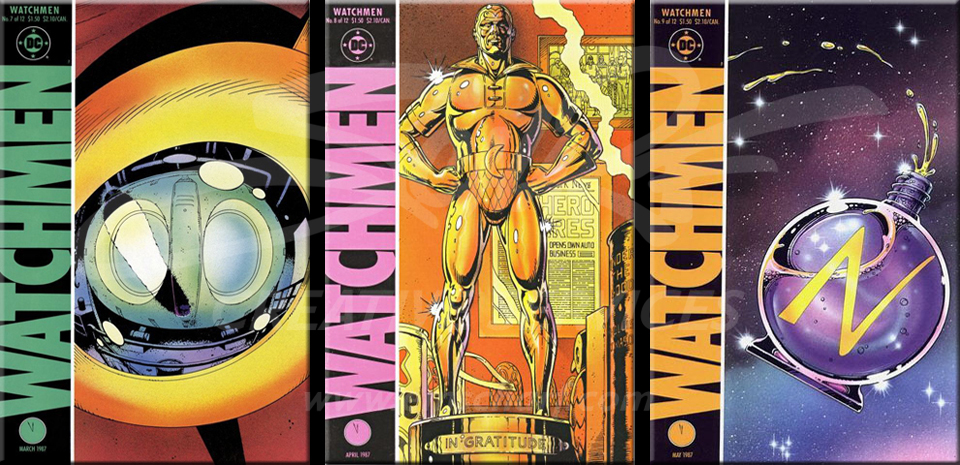

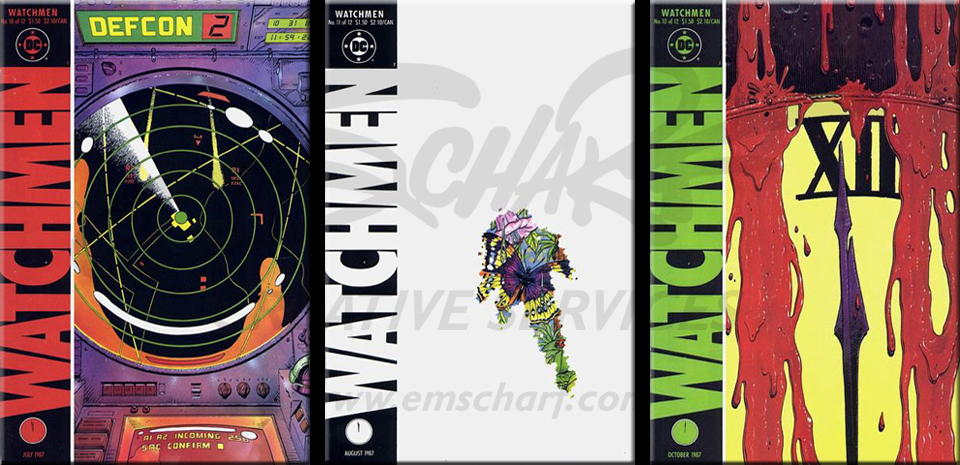

The Media Magnate had only once read through the 1986-1987 "Watchmen"

12-issue comic book mini-series (written by Alan Moore,

penciled-and-inked by Dave Gibbons, and colored by John Higgins) before seeing the

Hollywood

embodiment. The resultant vague memories allowed for viewing the film

with an open mind . . . minus the pre-existing paperback

postulations which have historically haunted so many silver screen

successions.

While Gibbons and Higgins quite

appreciated and enjoyed Zack Snyder's adaptive (and collaborative)

effort to bring their illustrative work (further) to life, Moore planned to "spit venom all over" Hollywood's handling of one

of his most fan-cherished stories. Moore has long-standing legal and

philosophical issues with DC (and in turn Warner Bros), and

Snyder no matter his very best and most respectful of intentions

was going to be collateral damage.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Before delving into the films story (or in the case of "Watchmen"

group psychological evaluation), the visual

quality is rich and vivid, delivering a satisfyingly immersive

experience, with characters you can reach out and grab, grimy

surfaces you can touch, blood, sweat, and tears you can feel, jet

fuel and bad breath you can smell, and gritty, emotionally-charged

voices you can hear, not to mention the near panel-for-panel

match to (most of) the original material.

The mix of slick-modern superhero costumes and

trench(coat)-level 'get it done' outfits is a nice departure from

the sterile, (almost) always-clean costumes on display within the

current "X-Men" film series. Some heroes absolutely need to look the

part while others (in sensationally soiled civvies) just look at you and say, Bring it.

But enough about the "sugar-coated topping" as Marvel's "Blade"

once said, and onto the

underbelly.

"Watchmen" takes place in an alternate universe in 1985, where the

United States is still embroiled in the Cold War with the U.S.S.R.,

Nixon is still President of the United States and with term limits

abolished in part due to his success in Vietnam he is on his fifth

term in office.

-

-

-

Tensions are as high as most Americans can remember,

the doomsday clock is set at five minutes to midnight, and

nowhere in sight is the statement Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this

wall!

-

-

- Vigilante superheroes in the flashback lead-up to 1985

happened on

the scene and grew in prominence from 1940 through 1960, culminating

in their much-needed participation in the U.S. winning the Vietnam

War. Soon after, the superheroes learn that unless they are willing

to work for the U.S. government they will effectively be legislated

into retirement through the Keene Act. War-time appreciation when

it exists continues to have its limits.

The plot is established in the midst of this forced retirement, when

an established super hero-turned-U.S.-government-mercenary Edward

Blake / the Comedian (played by Jeffrey Dean Morgan) is brutally murdered. He puts up a valiant fight, but

he is overmatched by a masked intruder who tosses the Comedian through the plate-glass window of his

own high rise apartment, leaving a bloody mess on the street below, which prominently sports one of his patented smiley face pins, stained with

the Comedian's "bean juice," and tormenting his colleagues one final time.

-

-

- The Comedian as we come to understand him

is far less a literal

comedian (with whom his colleagues can laugh at the expense of a

common enemy), and far more a complete jackass who with his

Punisher-like combat skills always seems to go two steps further

than his government-issued orders require, and who mercilessly hee-haws at

the misery his actions cause. He has no hero complex, goes

to work with a smile on his face, and does not take kindly to anyone

expecting him to take responsibility for his actions.

-

-

- Nonetheless, torment turns to paranoia as

all but two members of the former

Watchmen are on high alert about their own safety even with their

secret identities hidden away in

retirement with the most incorruptible and relentless of them all,

Walter Kovacs / Rorschach (played by Jack Earle Haley), leading the search for a

possible super hero serial killer or an organization of

killers.

It is

only fitting for the most strong-willed of "The Bad News Bears" to make his

triumphant return to the silver screen as the equally-willful and

undeniable Rorschach.

-

-

- The film adaptation of one of the most celebrated graphic novels of

all time at this point is already drowning in grit, keeping the

pedal to the metal for the duration, with the not so subtle reminder

that time waits for no one . . . and no good or bad deed ever goes unpunished.

Ferris Bueller once said, Life moves pretty fast. If you dont stop

and look around once in a while, you could miss it.

The further Rorschach digs, the clearer the murderous trail becomes,

the faster each event unfolds, and the more on-edge the Keene

Act-defying vigilante heroes (and moviegoers alike) become. The sad irony is that

while

the Watchmen are determined to find the answer for their fallen comrade and

obligated to protect themselves from the very same fate the closer

the heroes get towards the source of their troubles, the more they

question their collective purpose, and the less they like what they

find.

The Watchmen have only each other to relate to and

rely on in a world not at all richly endowed with super

heroes. Each of them is desperate in their own way to grab onto

something that is more than just their now-fragmented team, to

belong to something that represents more than just an association of

oddballs, and hold on for dear life (which is a common thread that

weaves together most-but-not-all superhero stories).

And their government-enforced exile, essentially, displaces

all of them, creating an internalized

tension that grows by the

day.

The Comedian being a government-sponsored hero is not restricted

by the retirement rule, but he contributes to his teammates

difficulties early and often, far in advance of his death. He

follows his orders with such single-minded (and admittedly reckless) focus that by the time he finally

comes to grips with what he has 'accomplished' on his missions it

is too much for him to digest all at once, causing him to

crack, spill secrets (to a retired super villain no less), and unknowingly triggering his own termination. Live hard and die hard(er).

Rorschach by (extreme) contrast has never been empowered by

government-funded opportunities to fight crime, whether as an

officially approved

superhero or as a vigilante for whom authorities occasionally

turn a blind eye in order to keep their hands clean(er). Rorschach

has only ever been energized by his all-consuming perspective of

humanity as moral or immoral, black or white, with rapidly

diminishing interest in the circumstantial gray. While Rorschach's miserable childhood forged

his fractured foundation, the life event that pushes him completely over the edge involves

a kidnapped little girl he is unable to save from being dismembered by her

captor (who then feeds her remains to a couple of man's best friends).

There is stifling irony in Rorschachs world view of humanity as the

single greatest obstacle to his mission of cleansing Earth of

immorality. The level of purity he

insists on seeing from imperfect beings could not exist in any form that would

reasonably satisfy his definition. If Rorschach

allows himself a moment of clarity to see his cleansing mission of

going from 'one ivory tower to one street corner at a time' will

never end especially with potential interference from one or more

of the Watchmen he

would practically beg to be put out of his misery.

Rorschachs perspective on humanity makes for an odd-if-intriguing

pairing with someone he considers a good friend, his best friend,

and perhaps his only friend in Daniel Dreiberg / Nite Owl (II),

played by a real hoot in the rangy Patrick Wilson. They both

prefer to first investigate a given crime scene, but the

approach is where their similarities end. They both excel in deadly

hand to hand combat, but the compact Rorschach is much more of a bruiser while the

larger Nite Owl is more of a

tactician. They appear to accept

each other without much precondition and without much verbal

acknowledgement they tend to agree to disagree (and agree again)

on how to best engage the very people they have vowed to protect

from evil. Yin and yang, manage and maim, read and react.

Nite Owl and Rorschach.

Two key scenes when tensions

are already particularly heightened perfectly demonstrate their

demented portrayal of "Laurel and Hardy."

The first scene occurs in Nite Owl's subterranean hideout where

Rorschach picks on Nite Owl's compassion-first perspective.

Rorschach: "You forgot how we do

things, Daniel. You've gotten too soft. Too trusting, especially

with women."

Nite Owl: "Ok. No. Listen! I've had it with THAT.

God! Who do you . . . WHO do you think you are, Rorschach? You, you, you live off

people while insulting them! And no one complains, because they

think you're a goddamn LUNATIC! I'm sorry. I

shouldn't have said that, man."

Rorschach: "Daniel . . . you are a good friend. I know it can be

difficult with me sometimes."

Nite Owl: "Forget it . . . it's ok, man. Let's do it your way."

Nite Owl and Rorschach take Archie

out for an interrogatory run, with the audience being led to

assume

it will once again result in Rorschach taking it too far and Nite Owl stepping in to diffuse the situation.

In the very next scene, "Rorschach

and Nite Owl walk into a bar," asking if anyone knows of

Pyramid Transnational. One not-so-smart patron draws the wrong

attention to himself. After being mistakenly antagonized by that

patron, Rorschach questions him (while crushing a glass in the

patron's hand and snapping a couple of his fingers for mouthing off

in-between painful gasps of useful information).

Rorschach and Nite Owl are about to

leave when they notice and stop to watch a news bulletin announcing former "Minute Man" and original Nite Owl Hollis

Mason is found murdered in his home. The reporter mentions

bystanders seeing members of the local gang the "Knot Tops"

leaving the area right around the estimated time of death.

The normally reserved Nite Owl who

looked up to Mason and considered him a great friend (even a father

figure) suddenly looses it, wheels on a member of the Knot Tops

(minding his own business at a table just a few feet away), and

demands he tell him who was responsible for Mason's murder.

-

-

- The Knot

Topper stupidly decides to give Nite Owl some unadvisable lip, defiantly spouting off about his civil rights, but as if

"overcome by bloodlust" in another Snyder film Nite Owl has none

of it. The Knot Topper is already on thin ice, and shooting his mouth off opens up a

rare powder keg of (the normally reserved) Nite Owl.

Nite Owl beats the Knot Topper

within an inch of his life before

Rorschach as if shot from an extremely black comedy cannon suddenly

restrains Nite Owl and (in all seriousness) says: "Daniel! Not in front of the civilians."

-

-

- Nite Owls situation for all of

his complex gadgetry is the

simplest yet no-less frustrating. Outside his nifty nest

whether tinkering with tech under his two-flat or taking to the night sky

in his awesome aircraft (called Archie, short for Archimedes,

Merlin's pet owl) he is the very capable yet reluctant warrior. Even after having tangled talons with so

many villains, Nite Owl is still uncomfortable in his own

feathers (and admittedly feeling less-than without his

tech). His read-and-react mentality explains why Nite Owl

is content with the relentless Rorschach being

the aggressor. That is, of course, until Rorschach (inevitably)

takes his information extracting tactics too far, causing Nite

Owl to attempt to 'break it up' (and hope Rorschach is

willing

to oblige).

Nite Owl is forced to molt his hesitation in order to help Rorschach

solve the Comedian's murder for the greater good of the team. It took Nite Owl's jump-started relationship with Laurie Jupiter / Silk

Spectre (II) played by Malin Akerman to give him the

confidence to finally break out of his rather impotent

daily routine, succumb to his burning desire to resume the role of Nite Owl

(without fear of government reprisal), and attempt to make a difference alongside his fellow

vigilantes.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Silk Spectre is the one Watchmen

hero who reminds of a child nurtured down a specific

career (path by her single parent) at which she clearly excels even though she may never have been

interested in pursuing it. The story of a great many children

involves the absence of parents who encourage them to (reasonably) find their own

way but when a child is forced to become a super hero, it

seemingly stands in contrast to what the majority of modern day children experience.

-

-

- Silk Spectre's mother Sally

Jupiter / the original Silk Spectre (played by Carla Gugino) operated as a crime fighter during a time period when liberal women

were not a welcomed part of society. Her mother in her own

way empowered women everywhere to believe they could stand up for themselves, accomplishing more than just the

status quo of the time.

-

-

- Sally was determined to see Laurie follow in her own crime-fighting

footsteps. She (understandably) saw her daughter fair or not,

selfish or not as the very best vehicle for passing on fighting

skills and (eventually) equal / near-equal stature among those who

would be her future male crime-fighting companions. Laurie certainly

has the same refined-and-deadly fighting skills to put the bad guys

in their place, and she looks equally good putting them there, as

well.

One would think that even in mandated retirement the government

might approach her with (secret) agent opportunities of some kind. For all

the skills Laurie brings to the table, however, consider that if not

for being the (hopefully) humanizing love interest of Jon Osterman /

Dr. Manhattan (played by Billy Crudup), and without an eventual Nite Owl connection or any normalized relationship with her

estranged mother Silk Spectre potentially faces a rather isolated

existence.

Never to be confused with Dr. Detroit, what does Dr. Manhattan the most

brilliant-and-powerful entity known to humankind do to remain

interested in Earth, its inhabitants, their commonalities and their

(seemingly petty) conflicts? Does it matter that Dr.

Manhattan spends half of the film transporting himself around town without

so much as a

loin cloth? If you ask him which he prefers boxers or briefs you

might discover that, when you wield as much infinite power as he

does, the basic needs of modern day humanity (food, water, clothing, shelter,

community, education, sense of purpose, transportation) laughably hold

no value. That is, unless a god with a still-intensely-curious

scientific mind is

in need of friendship, companionship, or entertainment from his

former human peers (all but perhaps one of whom he views in the same

way as "the world's smallest flea," but more on that later).

-

-

- The end of his relationship with humanity begins the very moment

scientist Jon Osterman is transformed into Dr. Manhattan by way of

being trapped within a 'Intrinsic Field Subtractor (IFS)' within the

army base where he and his colleagues perform their critical work in the

field of nuclear physics. Osterman's body is disintegrated on the spot,

without a trace. His colleagues grieve, time passes, and then, suddenly,

various internal elements of his body begin reappearing, reconstructing as if lightning strike

hallucinations and with each (frightening to the public) bolt from

the blue more elements compose

themselves and come together . . . until he is finally 'whole' once more.

-

-

- The idea

that Osterman does not run, err, float off screaming insanely into the wild

(fluorescent) blue yonder considering his sudden massive awareness of

'everything' around him (including on-demand sight into both his

past and future) is impressive even if the reason is

simply because Osterman is struggling to regain his bearings.

-

-

-

-

-

- Osterman succumbs to the (immediate

but not perpetual) need for

more structure through the 'welcoming arms' of the Department of

Defense (DoD), assuming his desire to blunt his own confusion and receive

exploratory goals towards handling his new-and-terrifying abilities. All the DoD

requires in return for "shaping (Osterman) into something gaudy,

something lethal" is Osterman's willingness to help his countrymen in

times of war to further their weapons development efforts and to

give them his naming rights. He is thusly branded Dr. Manhattan . .

. as a historically horrifying deterrent to enemy nations familiar with the Manhattan

Project.

-

-

- Dr. Manhattan's quickly-achieved control over his galactic gift

triggers the ultimate responsibility of which was referenced

earlier. He can choose to ignore or be of determined purpose to

humanity. He can be good, willfully oblivious, or evil towards a race of largely ignorant,

navel-gazing, self-destructive beings who will forevermore reside on an incalculably

different, lower plane of existence.

This concept

conjures memories of Galactus, the Beyonder, Thanos, Darkseid, and

Uatu the Watcher: all incredibly powerful cosmic entities and each

with a different approach to using and maintaining their abilities .

. . whether or not that involves synthesizing planetoids for

consumption, toying with the lives of simple beings, wreaking

unimaginable destruction, causing merciless death (by the mere

twitch of an appendage), or being a docile observer of such universal events (sworn against

interference unless faced with unfathomable circumstances).

Though

Dr. Manhattan has a gentle bedside manner, he as with his godlike counterparts

ultimately needs (light years of) space from the

'disturbance' or 'irritation' of humanity in order to truly

live. Who would have thought that when you get too big for your britches, you seriously consider leaving your home planet behind, rather than just purchasing a larger pair of pants? While "Planet

Hulk" is not being referenced here, the Hulk certainly would

appreciate the ability to leave "puny [hateful, ungrateful] humans" behind in the blink of

an eye, far more than a fine pair of incredibly flexible pants.

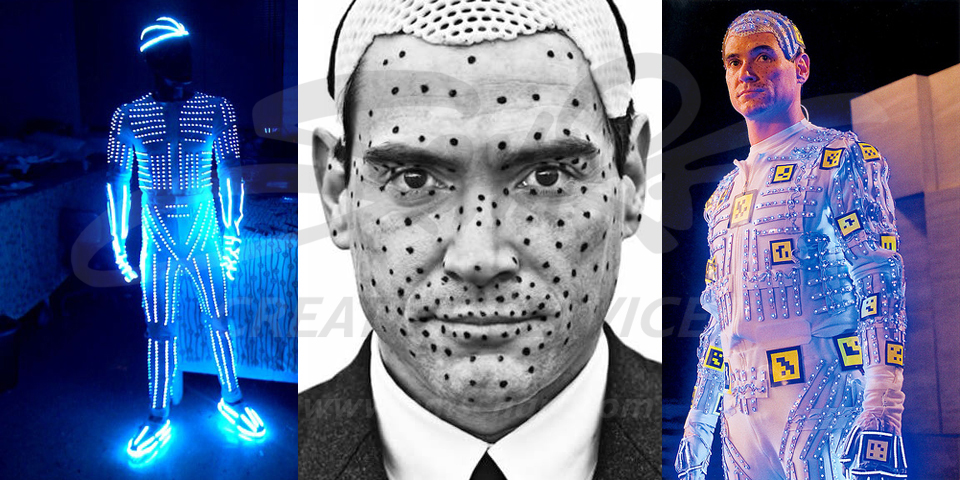

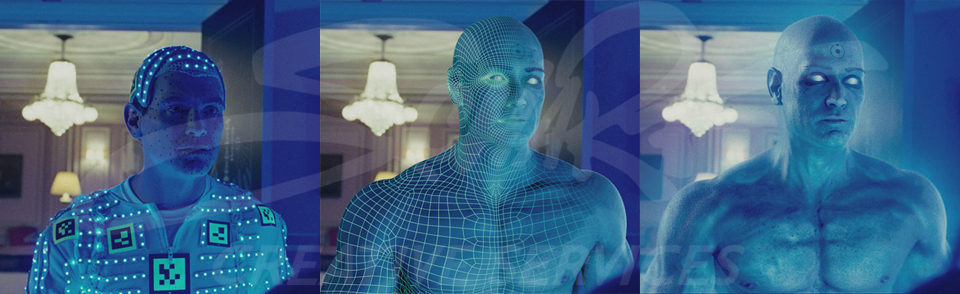

Speaking of colorful characters, The Media Magnate's only mild visual reservation

is with how Dr. Manhattan is

(rather bravely) 'rendered'

in 3D using Autodesk's Maya and Side Effects Software's Houdini

atop a practical, actor-worn lighting rig. Dr. Manhattan's body is an all-CG creation

with a custom, quad-polygonal 3D model (based upon digitized scans of Billy Crudup's face

and fellow actor / model Greg Plitt's

body), all driven by motion capture.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- It is genuinely understood and

appreciated (from The Media Magnate's own time in the games

industry, using very similar technology and lower-detail visual

assets) just how hard it is to generate and maintain maximum control

over a photorealistic,

self-illuminated, fluorescent blue 3D character without

significantly impacting the lighting requirements of the surrounding

environment, atmospherics, props, and other characters within a live action scene.

A carefully integrated VFX approach as subtle as Dr. Manhattan's

needed to be proves the difference between

near-hit believability and a near-miss distraction. The combined

techniques used by Snyder were worth the risk and produced

admirable-if-understandably-imperfect results.

-

-

- Dr. Manhattan

nonetheless and at one point during the film agrees to (slow his

on-camera glow and) be a

broadcast television show guest to answer a series of questions from the

show's host and

live audience. An aggressive reporter within the audience confronts Dr.

Manhattan with probing questions about his past colleagues

(pointing out how everyone with whom he had been in regular contact

since becoming Dr. Manhattan had gotten cancer and died). The

reporter even rolls out Dr. Manhattan's old girl friend Janey

Slater (played by Laura Mennell) who spews venom over her horrible

fate and pulls off an

unexpected wig to gasp-inducing effect.

Dr. Manhattan is caught off

guard by all of this, repeating that he had never been

notified. The reporter and the rest of the audience (seemingly,

stupidly

unfazed that Dr. Manhattan could vaporize them with but a gesture)

rush the stage with flashbulbs-a-popping and more questions. Dr. Manhattan as if

trapped by a suffocating school of fish (finally) snaps.

"Please. If everyone would. just.

go. away . . . and leave me alone. I said . . . LEAVE ME ALONE!"

Dr. Manhattan.

-

-

- Dr. Manhattan teleports himself to

the silence of Mars. Though he easily could have chosen to leave

Earth behind out of (artificially engineered) fear of causing everyone near him cancer,

he was already on the verge of testing the concept of distance making the

heart grow fonder.

"I am tired of Earth. These people.

I'm tired of being caught in the tangle of their lives." Dr.

Manhattan.

Long before Dr. Manhattan determines, however, that he no longer has

a place among humans, he has a number of opportunities to

halt questionable or even horrific actions by both his teammates and

his government, and, yet, he chooses not to get involved. This is

both unconscionable and understandable, and the first real signs the

'human affliction' or 'human condition' can no longer count Dr. Manhattan among its

life-long victims.

Dr. Manhattan still has a moral

compass, and he

knows he can make the biggest difference in a safe(r) future for

humankind. He knows the U.S. and U.S.S.R. are on the bleeding edge of

doomsday,

and yet, as Adrian Veidt / Ozymandias (so smoothly played by

Matthew Goode) says, Not even Dr. Manhattan can be

everywhere at once. So prophetic.

-

-

- Ozymandias having previously

exposed his true identity to the public is one of two Watchmen

(besides Dr. Manhattan) who have no need to hide following passage

of The Keene Act. Ozymandias has made an incredible business empire

for himself (in part from Watchmen-related action figures),

generating exponential insulation from almost anyone or anything on

the planet, public or private.

Ozymandias like Dr. Manhattan has absolutely nothing to

loose, while his colleagues continue to watch their backs even in

seclusion. The same cannot be said for those who visit Ozymandias at

his office building (when in his Adrian Veidt persona), like the

"Big Fossil Fuel" representatives who regarding an aggressive switch

to renewable energy sources come to first complain, then threaten,

then (after a 'subtle' reminder of Veidt's ability to purchase their

businesses three times over) feebly apologize. They are all killed

for their trouble by a hit man who conveniently comes up short

against the superior-skilled Veidt, who comes down hard on the

hit man with one superb swing of a nearby queue pole. The hit man

ingests a poison pill rather making any proclamations before

expiring.

-

-

- While Ozymandias is down one secretary and freed from a fraternity of

fraudulent fossils,

he is already refocused on what he aims to be his defining

accomplishment, his life's work.

One thing still vexes the great Ozymandias, even with

his absolute release from the need for super hero secrecy (though

his need for business secrecy is another story). What does "the smartest man on

the planet" do to scratch a maddening mental

itch? Ozymandias' fascination with one day becoming the modern day

match of his idols Alexander of Macedonia ("Alexander the

Great") and Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II (from whom he procured

his super hero name) ultimately drives him towards his own mad interpretation of

how to attain world peace among near-warring nations. He decides to provide the world's two national super powers

on the brink of nuclear destruction with an unbelievably

convincing incentive to immediately unite towards establishing world peace.

He prepares to deliver his insidious inducement through cataclysmic

devastation normally only associated with nuclear weapons, a 'global

killer' asteroid . . . or one

particular member of the Watchmen.

Ozymandias schemes to use Dr. Manhattans own personal struggle

between remaining on

Earth as humanity's super social worker or

heading out of Dodge to go "where no man has gone before"

to establish the perfect alibi to do the unthinkable.

He aims to destroy major cities around the world, including New York, Los Angeles,

Paris, Moscow, Hong Kong, and Tokyo in

the ultimate attention-getter among squabbling super powers

(specifically the United States and the U.S.S.R.). Dr. Manhattan

in the only end game Ozymandias can envision represents the

perfect scapegoat for his meticulously manipulative plan.

Dr. Manhattan is impervious to any physical threats from humanity.

He is kind to humanity (or at least the U.S. and their western allies),

but kindness can diminish to mere tolerance, and mere tolerance

in the blink of a super-powered eye can transition into

cleansing the home world of a ridiculously self-destructive race. He represents

the

common denominator required to forcibly bring two adversarial

'superpower' countries

and many other smaller players together towards formation of the ultimate peace

accords.

-

-

- Ozymandias enlists a group of top scientists

to collaborate remotely with Dr.

Manhattan on a "clean energy project." His scientists operate from

within the isolated confines of Ozymandias' Antarctic fortress, Karnak

(named after Egypt's "Valley of the Kings") with the collective goal

of designing and constructing an "Intrinsic Field Subtractor (IFS)," similar to the one that originally transforms Osterman

into Dr. Manhattan . . . but which critically mimics Dr. Manhattan's

energy signature and teleportation ability.

-

-

- Once the IFS is operational, Ozymandias intends to

dispose of his hired help using the shiny new coffin they

have unwittingly designed for themselves.

Ozymandias aims to frame (the relentless bloodhound) Rorschach

for the Comedian's murder before he can unmask how it is Ozymandias who, in fact, ends the hilarious hit man (who

discovers his sinister plot at the specific request of Tricky Dick

Nixon). And that it is Ozymandias who pays-and-kills his

would-be assassin with a cyanide pill. And, AND how it is Ozymandias who

also

kills the cancer-stricken former super villain, Edward Jacobi /

Moloch the Mystic (played by Matt "Max Headroom" Frewer)

in whom the suddenly cracked-and-crying Comedian confides his

world-shattering realization. And, AND, AND

how Ozymandias causes Moloch, as well as Dr. Manhattan's friends,

colleagues, and handlers Janey Slater, Wally Weaver (played by

Rob LaBelle), and General Anthony Randall to also die of cancer.

Ozymandias would then teleport in, trigger, and

teleport out the IFS to progressively, respectively destroy New York, Los

Angeles, Moscow, and Hong Kong . . . in order to frame Dr. Manhattan

as the undeniable source of the worldwide devastation.

Most critical to keeping the electric blue foundation of Ozymandias'

devastating design in a reliable mindset is the placement of tachyon particle

generators throughout the Washington, D.C. area from at least the

beginning of the IFS construction and through the end of

intercontinental

destruction. The presence of these devices prevents Dr. Manhattan from seeing (or

distinguishing current events from) his own future. This masking of

his 'timeless sight' restricts Dr. Manhattan to only those events which

he experiences in real-time and (as Ozymandias hopes) could cause him to

finally decide humanity is unworthy further

'encouraging' him to pursue permanent self-exile from Earth as his only

non-violent escape (from humanity's boorish violence), and

perhaps of greatest value to Ozymandias . . . no (further threat of) interference from

the only being really capable of dooming his design.

Assuming no unexpected gotchas derail his mad scheme too soon, Ozymandias

will attempt to convince the other Watchmen of the bigger, better

picture and to keep this most horrible secret from

the rest of humanity (rather than risk an unthinkable doomsday clock relapse), and if they fail to appreciate his grand vision he will kill them to ensure

silence.

While Ozymandias is

busy unwinding his twisted tale, Rorschach and Nite Owl are

aggressively following (surprisingly sloppy) bread

crumbs back towards Pyramid Transnational (a subsidiary shell

company of Veidt Industries under which Ozymandias has been coordinating his

entire plan).

Ozymandias underestimates just how quickly Nite Owl and Silk Spectre

decide to throw Keene-Act-caution to the wind and attempt to break

Rorschach out of prison (where he is, of

course, held after Ozymandias frames him for Moloch's murder).

Following their

successful retrieval of Rorschach during a prison riot in which

Rorschach 'saw handfuls' of activity and they

return to Nite Owl's nest to regroup.

Dr. Manhattan suddenly reappears

from his Mars meditation just in time to ruin a gentle kiss

between Nite Owl and Silk Spectre. Time away from mind-numbing tachyon

interference clears Dr. Manhattan's head, finally allowing him

enough focus to urgently approach Silk Spectre about a forthcoming

discussion.

"You're going to try to convince me

to save the world." Dr. Manhattan.

Silk Spectre agrees to go back to

Mars with him under unknowing protest from Nite Owl. Dr. Manhattan

transports her to Mars and within immediate view of a mammoth animated

crystal time piece (harkening back to memories of his youth and the

mechanical teachings of his watchmaker father). Dr. Manhattan is 'slow' to envelope her

within a

breathable air pocket, drawing further attention to his potentially expanded

disconnect from humanity.

Silk Spectre is already angry with him and

demands he just cut to the chase and confirm whether or not nuclear

destruction is imminent or humanity survives to continue on its

imperfect journey. He shares that from what future bits and pieces

he can finally see she ends up in tears and "the streets are filled with

death." She implores him to return to Earth to prevent

mutually-assured destruction.

Dr. Manhattan explains that he

merely sees life on life's terms, but that she refuses to see things

from his perspective, that she shuts out the things she

fears. Silk Spectre dares him to "do that thing you do" and

expose her to his omniscient memories. After obliging her demand,

they both exit his forced

flashback emotionally distraught. She is in tears over the realization

her father was the Comedian, and Dr. Manhattan is in shock over the

realization he is wrong about miracles (of life) and humanity's

ability to create them.

Her birth from as contradictory a union as rape was a miracle, and that creating life is "like turning gold into air."

While the miracle of life would seem to be a completely obvious

thing to a being like Dr. Manhattan, it is entirely possible the

stench of humanity's extremely poor showing on the cosmic stage (let

alone Earth) may so disgust him from making any

further effort to help save the human race . . . that it takes an equally ugly thing in

the rape of a woman for him to see the value in humanity's

imperfect and unpredictable ability to create life.

Dr. Manhattan

returns to Earth with Silk Spectre to fulfill one last promise

to her, and make one final doomsday-diverting delivery to a

still-undeserving humanity.

They appear in New

York City and before he can act, however humanity appears to

have beaten him to the punch. A significant portion of the city has been

obliterated by what appears to be a nuclear blast (to the untrained eye

straining to view imperceptible differences). The DoD

almost immediately determines (by energy signature alone) the chaos

could only have been caused by Dr. Manhattan (who to the contrary finally

notices the tachyon interference that has been preventing him from realizing

what has really been occurring since the beginning of his IFS

collaboration with Ozymandias). He explains to Silk Spectre that he

has been framed by Ozymandias, and he instantly teleports them to

Ozymandias' Antarctic compound to confront him.

-

-

- Upon their arrival, Dr. Manhattan

and Silk Spectre see Nite Owl and Rorschach, who had arrived earlier and come to the same

conclusion (albeit by breaking into Ozymandias' office, gaining access to his

computer's database through some timely password tinkering and

shockingly connecting all the bytes to Pyramid

Transnational).

Nite Owl and Rorschach think they

have Ozymandias surrounded and outnumbered, but Ozymandias easily dismisses their initial

assault with his incredible reflexes. It seems he is either a great "Remo Williams"

impersonator, or his genetically-engineered pet lynx, Bubastis, was not the only thing he genetically

created or enhanced.

-

- Dr. Manhattan nonetheless marches

up a main staircase past Nite Owl

and Rorschach. He hears but does not heed their warnings, and asks them to stay put

(knowing full-well Ozymandias may yet have more devastation on tap

for the only being capable of stopping him). Dr. Manhattan makes his

way into a suddenly tight corridor for such an open compound as Karnak. He is kept momentarily preoccupied by Bubastis.

-

-

-

-

-

- The sight of Bubastis as a brief

aside was a pleasant

surprise versus what would have been an understandable VFX

dodge.

-

- Nonetheless, it is in this moment

that Ozymandias quietly asks for Bubastis' forgiveness as he flips

the fatal switch to the IFS, hoping but not knowing if the

kind of construct that can create Dr. Manhattan can also obliterate

him.

-

-

-

- Dr. Manhattan seems prepared for and completely at peace

with

Ozymandias' perceived master stroke, while Bubastis can only

helplessly growl in protest at her own disintegration. It takes but a (long)

second to occur . . . and they are gone.

-

-

-

-

-

- Dr. Manhattan seemingly can as he says "turn the walls (of the IFS) to glass." Perhaps

he is curious as to Ozymandias' next steps, and he is willing to expose

himself to a cataclysmic conclusion in order to learn Ozymandias'

true end game.

-

- Perhaps Ozymandias also employs

tachyon interference devices within Karnak, as well, continuing Dr. Manhattan's inability to retain full mental control and focus.

After all, Dr. Manhattan could have floated rather than take the

stairway up into the IFS chamber.

-

- Perhaps his reaction is another

example of his growing disconnect from humanity, which reminds of

the scene following the Dr. Manhattan-powered U.S. victory over

the Vietcong where the Comedian is confronted by a Vietnamese

woman he impregnated. She wants to know what he is going to do

about their baby. The Comedian wants nothing to do with the

situation, talks down to her, and tries to dismiss her. She has none

of it, breaks a beer bottle, and slashes the Comedian's face. He

draws his gun and takes aim as if she is just another member of the

Vietcong.

"Blake, don't.

BLAKE! She was pregnant . . . and you gunned her down."

Dr. Manhattan.

"That's right. And you know what?

You WATCHED me. You could've

turned the gun into steam, the bullets into mercury, the bottle

into goddamn snowflakes. But you didn't, didja'? You really

don't give a damn about human beings. You're driftin' outta' touch,

Doc. God help us all. MEDIC!" the Comedian.

Ozymandias after seemingly

succeeding in obliterating Dr. Manhattan reappears at the top of

the staircase within Karnak's main chamber, to the shock of Nite Owl, Rorschach, and Silk Spectre (who decides to dispense with

the awesome, collective show of hand-to-hand combat in favor of a

point-blank gunshot at their longtime teammate-turned-enemy).

Ozymandias to everyone's surprise

goes tumbling down the staircase, sliding to a limp-bodied

halt. Their surprise is shattered as Ozymandias reveals

he caught the bullet with a well-padded glove, as he suddenly side-thrust-kicks Silk

Spectre several feet up the staircase where she sustains a brutal

landing.

In one of the best, most painfully

dismissive lines of super hero film history following Nite Owl's threat to kill

Ozymandias if Silk Spectre has been severely hurt by him the always aloof, deadpan Ozymandias says,

"Grow up, Dan. My new world demands less obvious heroism. Your

schoolboy heroics are redundant. What have they achieved? Failing to

prevent Earth's salvation is your only triumph."

The Media Magnate as an aside and in that moment felt as helpless as Nite Owl looked

in his part of the failed 3-on-1 bid to take down Ozymandias. One

might argue the Comedian many years older than Nite Owl with

similar-to-superior fighting skills at least

put up a real fight to begin the film. Still, Ozymandias toyed with the

attack-minded Comedian like a cat with a ball of yarn in the process

of easily bloodying him before single-handedly (yes, with a

SINGLE hand) raising him off the ground "light as a feather,

stiff as a board" style and mercifully (?)

tossing him through a plate-glass window to his height-accelerated,

bean juice-covered death.

This tone-setting scene for those familiar with

the original fiction would appear to indirectly reference "The Veidt Method," a concept of body-and-mind development practiced by Ozymandias

(and publicly advertised by Adrian Veidt) as THE way to achieve and

maintain one's peak mental and physical skills.

The Veidt Method would seemingly be

one of only two unadvertised-by-Snyder reasons for Ozymandias' lightning fast, Remo Williams-like reflexes and superior

physical strength, with the other reason being that Ozymandias'

genetic experimentation may not have been exclusive to the creation

of his pet lynx.

Nonetheless, just when Nite Owl,

Rorschach, and Silk Spectre potentially begin to loose hope in their

collective ability to topple Ozymandias, a familiar voice booms from

above. Both heroes and villain alike suddenly look up to see a

towering, monster movie-sized Dr. Manhattan staring down at them

through the no-longer-so-massive-looking skylight in the facility's ceiling. His hand

like a wrecking ball with bad intensions smashes

through it and barely misses a diving Ozymandias.

-

-

-

-

-

- "Reassembling myself is the first trick I learned. I didn't kill

Osterman," says Dr. Manhattan as he returns to normal size and

approaches his team member-turned-adversary.

-

- "Did you really think it would kill me? . . . I have walked

across the surface of the sun. I have witnessed events so tiny and

so fast they can hardly be said to have occurred at all. But you,

Adrian, you're just a man. The world's smartest man poses no more

threat to me than does it's smartest termite." Dr. Manhattan.

-

-

-

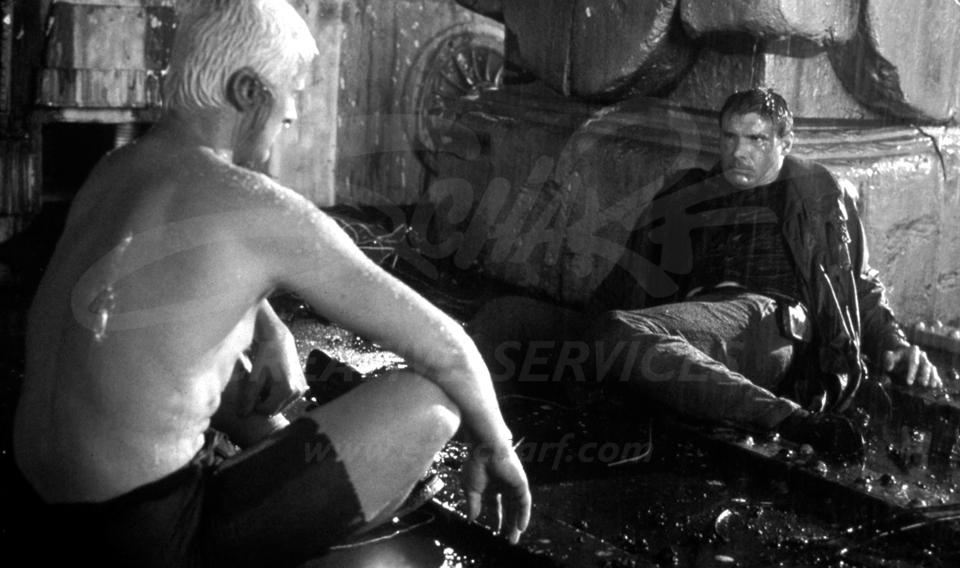

- As another brief aside, this scene faintly reminds The Media Magnate of

one of the final (powerful) scenes from "Bladerunner," involving Rutger Hauer's replicant "Roy Batty" and Harrison Ford's

"Rick Deckard."

-

-

-

- "I've seen things you people wouldn't

believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched

C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhδuser Gate. All those . .

. moments will be lost, in time, like tears, in rain. Time to die."

Roy Batty to Deckard, after sparing him from an equally deadly

fate.

-

- Ozymandias nonetheless and seemingly seconds

away from oblivion is holding up a handheld device

to which an unimpressed Dr. Manhattan responds: "What's that? Another ultimate

weapon?"

"Yes, you could say that," says

Ozymandias, who manages an uneasy grin (knowing he has been

similarly spared) as he presses a button on what

proves to be a TV remote. The bank of televisions he had previously

been watching suddenly attract everyone's attention with footage of

President Nixon confirming the inconceivable news, and that

like the rest of the developed world he has been fooled into

believing Dr. Manhattan is to blame.

It is in this moment that moviegoers

come to truly realize the tremendous potency of the tachyon interference, or recognize the astonishing naοvetι of a god-like being who is

expected to

know better in Dr. Manhattan. He would seemingly never allow

anyone or entity friend, foe, or friend-turned-foe to

successfully replicate his powers.

- The world's smartest termite indeed 'wins' the day . . .

insidiously sparing humanity from paying the ultimate price at a still-terrible cost.

-

- Ozymandias has degenerated

himself from being the most brilliant human on Earth to a person

terminally desperate to deliver the no, his ultimate

peace-brokering solution (but not a guaranteed or permanent one

due to the ever-present, unrelenting human condition that has

historically stunted society's ability to achieve greater harmony). He

in his madness determines there is also no better choice than to ruin the good name of

the most brilliant, powerful, capable, and docile-unless-provoked being known to humanity, encouraging the world to believe that Dr. Manhattan has

murdered millions of people in a fit of rage (as an extremely

convenient cover for the distributed blast from the IFS) just

so the threat of nuclear war could potentially be stopped

forever.

The Media Magnate sees a (very) loose connection between this result

and the final scene of the "The Dark Knight" the 2008 second leg

of Christopher Nolan's Dark Knight trilogy, when Harvey Dent

rather than dying a hero lives long enough to see himself become

the villain.

-

- "(Harvey Dent's) the hero Gotham deserves, but not the one it

needs right now (because the city can never know the truth). So we'll hunt (Batman). Because he can take it. Because he's

not our hero. He's a

silent guardian, a watchful protector. A dark knight."

-

-

-

- A similar sentiment with a twist exists in "Watchmen,"

with Dr. Manhattan being set up to take the blame for the

devastation wrought by Ozymandias.

-

- "Babysitting a society of troglodytes pretending to be members

of a civilization is not the responsibility Dr. Manhattan deserves, not

the headache he needs right now. So humanity will hate him, because

our trigger-happy superpowers can never know the truth. Because he can

take it in order to maintain the impossible achievement of a grand lie. Because he's not

our hero or one we have earned." as would have been

appropriately and privately stated by Ozymandias.

"I am tired

of Earth, these people. I'm tired of being caught in the tangle of

their lives." Dr. Manhattan.

-

- It is sad that such a brilliant mind as Ozymandias' succumbed to

the very brutal ironies mentioned at the top of this review. He wants

to save humanity from the potential of total annihilation, taking

measures that would only exist within the nuclear holocaust he seeks

to prevent, and, yet, he is performing this act for a society he

not-so-secretly

loathes.

Consider that Ozymandias has also come to this deadly conclusion to

forgive himself for failing to find a peaceful solution towards bringing

humanity together. He must feel as limited and helpless as the

normal, fellow human beings he despises. Then, again even though

it never appears to be part of his plan Dr. Manhattans exit

reasonably ensures Ozymandias will never again be or feel challenged by an

equal or superior intellect / higher power . . . until Dr. Manhattan's

unlikely (?) return, of course.

-

- Through the irony of all ironies, Dr. Manhattan and Ozymandias

deserve each other. Ozymandias uses tachyon radiation to block Dr.

Manhattans visions of the future, and, yet, we

have no way of knowing whether or not Dr. Manhattan had already seen

the future before his visions were blocked. Thus, Dr. Manhattan

could have, should have, but only might have stopped Ozymandias from

making his devastating decision.

Dr. Manhattan could have also

directly or indirectly prevented the Comedians death, and, by doing

so, Dr. Manhattan could have also prevented his own final (?) act on

Earth from being the mercy killing of Rorschach, who felt

totally betrayed when the most responsible human he knew,

in Ozymandias, could no

longer maintain his righteous separation from the abysmal humanity

both of them loathed, and in which Dr. Manhattan no longer had any

interest.

Superheroes again and regardless of how powerful always seem to be faced

with the perpetually impossible challenge of being more human than human, without becoming

inhuman. The Watchmen are doomed to self-destruction from the

beginning, leading to inhumanity in the end, but this is not because

they did not try mightily to avoid such a result.

Some

filmgoers were anticipating another superhero film for the sake of

superheroes, and Watchmen could not be farther from that kind of

experience. Other filmgoers wanted to see something that properly

honored the material on display in Alan Moores 12-book mini-series.

While Snyder took calculated risks for a number of reasons (some

filmmaker practical, some studio executive questionable, and shared

implication for others) like so many directors before him and still

to come his effort was a near panel-by-panel replication of

Moore's material. For those who felt Snyder's effort was still

deficient or unreasonably inaccurate, Good luck

with that in a near 3-hour time span. Still, others were looking

for a healthy mix of both which left the result as firmly planted in reality as possible. Just

like viewing a Rorschach, almost everyone sees something different and in

the case of Watchmen purists and critics (unfamiliar with the

original fiction) wanted to see something different.

-

- The Media Magnate drank deeply of Snyder's adaptation and is

eager to see how his detailed direction might measure up with other

cherished comic book properties.

-

- Right or wrong, good or bad, fair or unfair, cinemagoers should

steel themselves for the Pandora's box that Snyder's effort may have

irreversibly opened: comic book film adaptations that involve an

increasingly in-depth marriage of two former foes . . . superhero

wonderment and (sometimes painful) reality.

|